Professor C. continues his seminar series, in this case with E.M. Forster, and “A Passage to India.” The work has particular meaning here, in light of my own 1982 trip. But beyond that, as Professor C. says, lie implications for Gay Pride this week in the USA. Belonging, love, power, and cultural dislocation have always woven their difficult threads through society.

David Lean’s Passage to India (1984) opens with umbrellas moving past an office window where there’s a picture of a P&O ship. Raising her umbrella to see the ship is Adela Quested, about to book passage for India, there to visit Ronny Heaslop and find out if she really wants to marry him – and marry India.

The umbrellas and the rain capture much of what’s English about England. British imperialism, in its least imperial aspect, was a flight to the sun. Countless English and Scots went “out” to India or Arabia or Ethiopia or East Africa or Egypt. On the first day of a trip I took to Egypt, mostly with English travelers, I remember a nice English woman exclaiming, as she emerged from her room into the Egyptian sunlight, about the miserable winter she had just left behind. I think the romance of the sun made a fair part of what sent Richard Burton and T. E. Lawrence and Gertrude Bell and Wilfred Thesiger and so many others off on their quests.

Early in Forster’s novel is a hymn to the sun’s generative power: “when the sky chooses, glory can rain” – not English “rain” – “into the Chandrapore bazaars or a benediction pass from horizon to horizon. The sky can do this because it is so strong and so enormous. Strength comes from the sun…” Who would want to spend a winter in England if something warmer and dryer could reasonably be found? But sometimes we bring the rain with us: in the film, after Adela has recanted her accusations against Dr. Aziz and he has been set free, his English friend Fielding stands in pouring rain while Aziz rushes off to a party celebrating his release. When the film ends, the rain is falling outside Adela’s London window while she reads Aziz’s letter of forgiveness and atonement. The final shot shows her face, framed by lace curtains, looking out the window streaked with raindrops, as though they were tears.

Lean’s film was a big success. Vincent Canby liked it –“intimate, funny and moving” – save for the musical score. Roger Ebert called it “one of the greatest screen adaptations I have ever seen.” It did very well at the Oscars (eleven nominations, including best picture) and Golden Globes (five nominations). As Mrs. Moore, Ronny Heaslop’s mother, the wonderful Peggy Ashcroft was everybody’s best supporting actress. As Adela, the equally wonderful Judy Davis was nominated for best actress by the Academy. Lean was nominated as best director and for best screenplay by the Golden Globes. The musical score that Canby disliked so much – it has “nothing to do with Forster, India, the time or the story” – took both awards as “best original score.” The Amazon reviewers of the DVD are almost all of them impressed: “magnificent and exquisite wrought”; “must see”; “a gem”.

But colonial spectacles on the big screen are risky business. An Indian reviewer on Amazon proves it. “I am an Indian,” he wrote, “I adore the way Forster wrote about India,” but the film is another story. Lean has fallen “for the standard shrinkwrapped clichés about India that any western director indulges in.” The casting is awful: “an atrocious Alec Guinness trying to pass off as a Brahmin Professor,” and Victor Banerjee, “absurdly over-eager,” who “struts about” as Aziz. The whole thing is “borderline idiotic.” Having criticized film adaptations of Wharton’s House of Mirth and Ethan Frome for not living up to their great originals, I’m inclined to take an insider seriously (assuming that being Indian makes the critic an insider). Why is the difference in aesthetic judgments so pronounced?

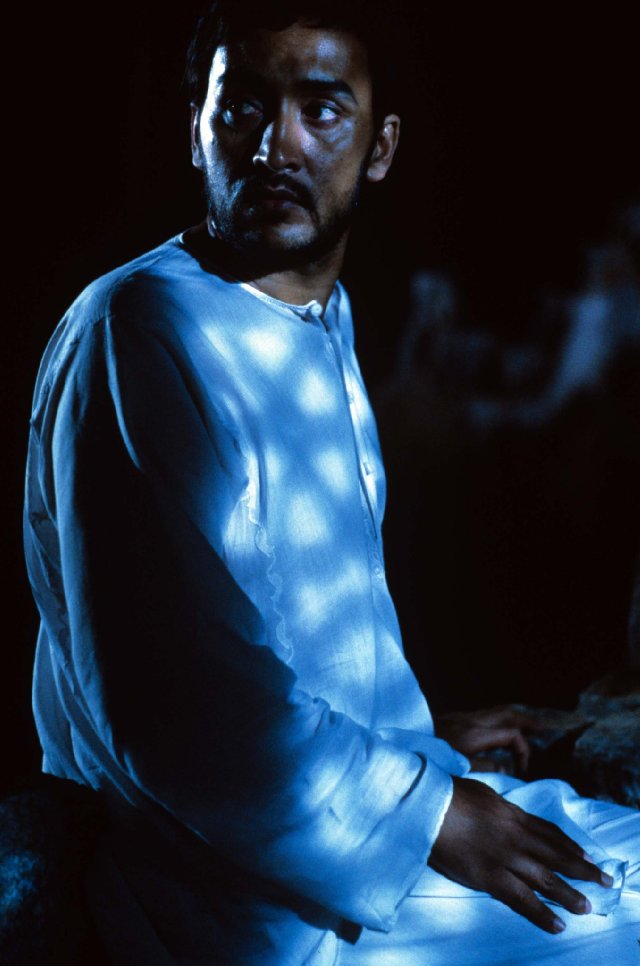

The casting, in one instance, is certainly a problem. It’s not just political correctness to think Alec Guinness makes an odd Professor Godbole (pronounced God-bo-lee, I learned from the film, which I suppose is right, though I’ve always thought it was God-bole). Guinness’s Godbole comes close to caricature. And maybe Lean realized this too late. It’s said their relationship deteriorated during the filming and that Guinness was unhappy when he learned how much of his part had ended up on the cutting room floor But Victor Bannerjee, born in Calcutta (now Kolkata), was almost perfect as Aziz to my eyes. Certainly he didn’t “strut.” If anything he cringed, like the obsequious Indian of the western imagination. Perhaps that was a problem for an Indian viewer. Or was it that Banerjee, an upper class Bengali, wasn’t the right choice to play the Muslim Aziz? I’ve never been to India. I know it’s a hard place to understand.

If I were Indian, I might think India had been slighted in the film. It begins in England, it ends in England. It begins with Adela Quested, it ends with her. Forster novel begins and ends in India. In the film, we see Adela booking passage. In the novel, there’s no “passage” in the usual sense, we’re already there. The “passage” of the novel is that of mind flying across space and time. Forster’s remarkable first sentence sets the stage: “Except for the Marabar caves – and they are twenty miles off – the city of Chandrapore presents nothing extraordinary.” Instead of English umbrellas and shop windows, we start with a panoramic view that narrows slowly to sights of the city itself, as if in some aerial shot of Google earth, a city where all is “abased,” monotonous,” a “low but indestructible form of life.” Nothing extraordinary except the Marabar caves, a surpassing exception. This is the last we hear of the caves until Aziz, having made the polite mistake of suggesting the English ladies visit him, proposes the fatal outing to the caves in order to spare himself the embarrassment of entertaining at his bungalow. Aziz has never seen them himself, but Professor Godbole has. Aziz tries to stir up Adela’s interest: no doubt the caves are “‘immensely holy?” “ ‘ Oh no, oh no,’ ” says Godbole. Are they ornamented? “ ‘Oh no.’” Then maybe the famous caves are an “ ‘empty brag’”? “’No, I should not quite say that,” says Godbole. Then “describe them to this lady,’” says Aziz. “ ‘It will be a great pleasure,’” says Godbole. But “he forewent the pleasure.” The famous caves are ineffable, beyond describing – even though the novel describes them: “A tunnel eight feet long, five feet high, three feet wide, leads to a circular chamber about twenty feet in diameter. This arrangement occurs again and again throughout the group of hills, and this is all, this is a Marabar cave.”

The film’s ending differs even more than its beginning from Forster’s. Fielding and his pregnant wife Stella, Mrs. Moore’s daughter, have been to visit Aziz in his new home in the Himalayas, away from the British. In the film, Fielding and Stella, starting their journey back home, drive off and Aziz watches them go. Then we see Adela at her window in London. The novel ends, instead, with a memorable scene between Fielding and Aziz. They go riding together. Fielding confides to Aziz that he and Stella do not get on very well. But she is pregnant, perhaps things between them will improve. Fielding and Aziz ride on. They talk about England and India, joking and fighting all at once. Aziz gives a mock-heroic cheer, like a schoolboy at a football match, for the new India to come: “ ‘India shall be a nation! No foreigners of any sort! Hindu and Moslem and Sikh and all shall be one. Hurrah! Hurrah for India!’” Fielding mocks him: India will “ ‘rank with Guatemala and Belgium perhaps.’” Aziz answers: “ ‘we shall drive every blasted Englishman into the sea, and then’” – he rode against him furiously – ‘and then,’ he concluded, half kissing him, ‘you and I shall be friends.’” Why not now, asks Fielding, holding Aziz “affectionately.’” But the horses and the earth and the sky “didn’t want it.” “ ‘Not yet.’”

When I began teaching in 1960, I was assigned, as were all newcomers, to teach a course called “Masterpieces of English Literature.” The choice of texts was up to me, but the course began somewhere near the start of English Lit. and ended somewhere near the end. I assigned Forster. But what did I have to say? Surely something about race, religion and reconciliation – but nothing, I’m equally sure, about what’s happening in that brilliant last scene between Fielding and Aziz. The horseplay, the half kissing, the affection, it was all lost on me. Forster’s homosexuality was not then generally known. His novel Maurice, with its theme of homosexual salvation, was not published until 1971, the year after he died. But I blame only my own naivete for not having understood. Yes I knew homosexuality existed — I wasn’t that naive – but the idea that homoerotic affection, however frustrated, could serve as a metaphor of reconciliation between races and religions, between colonizer and colonized, was beyond my grasp. In a great novel like Passage to India? I wonder how many gay students were in the class and understood better than I. If they did, it was not something in 1960 that would ever, ever have come up in the conversation.

Does this all mean that Lean’s film is as bad as the Indian reviewer on Amazon believed? I don’t think so. Definitely it is paler, notwithstanding all sorts of British-inspired pomp and pageantry. An Indian actor might have been found, someone able to make Godbole, as Forster calls him, a figure of “Ancient Night.” The crucial scene in the caves, when Adela thinks she has been sexually attacked by Aziz, might have been more deeply marked by a sense of its utter strangeness and mystery — except that’s not easy to bring off visually. Above all, perhaps, there might have been more of Forster’s sun and Indian light. Even so, not everything is lost. The film transforms an ineffable drama into a more domestic (and heterosexual) story of character and repressed sexuality that happens to happen on the great Indian stage. It is not a small achievement, though it strays far from the path Forster laid out.

Images:

Elephant, Feet in Pool, The Best Picture Project

Dame Peggy Ashcroft via Flickster

Victor Banerjee as Dr. Aziz, Judy Davis as Adela Quested, IMDb

Dr. Aziz and Adele via Turner Classic Movies.

Judy Davis as Adela Quested via Flickster

21 Responses

I LOVED this book. Going to download it to my IPAD to read again for my summer travels. Undoubtedly, my favorite Forster novel.

I enjoy your father’s posts very much. He must be such a lovely man.

Forster has sat on my shelf for several years, still unread. Professor C’s series has made me think that it might be time to remedy that. Thanks for sharing!

Hello Lisa:

This is a most interesting post. Forster for us remains one of the greatest English novelists of his time. We shouldprobably place ‘Howard’s End’ over ‘A Passage to India’ and whilst we enjoyed the films of both, we feel that they in no way equal the novels themselves.

May and Bob Buckingham, in whose house Forster died, we knew very well through a shared interest in music. Bob Buckingham, as you will know, was, of course, Forster’s lover.

I have seen the film multiple times, and love it, but never read the book. Now I will! Thank you for another interesting review.

Thank you for sharing such stellar insight on all of this, weighty topics indeed. While I pretend to be confident in thoughts and assumptions, it is always nice to see affirmation; your comments about the film’s casting are very similar to mine. In fact, as much as I loved the film (and do love the score), I think I remain miffed about Alec Guinness in the lead. But then I remember economic realities and understand why he was selected for the role.

This is a wonderful piece, I very much enjoyed it.

tp

I’ve read the book, but not seen the film. I think I’m tempted to do so now. And I absolutely love this series!

Thank you for this thoughtful insight into the film and all of it’s cultural implications. So many fabulous films from earlier times suffer from these kinds of casting catastrophes–even Breakfast at Tiffany’s, such a fun american classic is marred with one of the most offensive racist characterizations I have ever seen. I still love the movie even though I am part asian, but hope that in these more liberated times that film and people and will evolve past these missteps permanently.

Thanks so much for this, Professor C. It was always my favorite Forster novel, and I admit to having kind of a blind spot for David Lean’s films, which are gorgeous but, I realize, can be rather imperialist in outlook. I was fourteen when the film came out, and it and Gandhi were my first real exposure to the history of colonialism. Having just downloaded a bundle of Forster novels on my Kindle a few weeks ago, I had decided to reread them in chronological order and will be revisiting Passage at some point in the not too distant future. Your post will give me new perspective–especially regarding the possibility that the love between Fielding and Aziz wasn’t entirely fraternal–that is now stunningly clear, thanks to you.

What’s next? Another Forster book/movie pairing would be grand–there are so many from which to choose! But I look forward to anything you choose to take on.

Thank you for your observations, and for placing your history within it. I would like to see the film re-made or adapted for the stage; so much could shift, now. When I spent time in India (in this decade), I found the remnants of the Raj seductive. I was not proud of that, and at times took, at other times refused, the sumptuous services offered for, to North American eyes, so little. At least I had the awareness not to call them “cheap”.

Thank you for this thought-provoking, insightful post. Also, my thanks and respect to Professor C. I especially appreciate the mention of Gay Pride Week.

You might enjoy reading GREAT SOUL, the recent biography of Gandi.

Sorry for the caps in the title. I was unable to underscore.

I learn so much from reading the Professor’s particular framing of thoughts, how he isolates issues amid the myriad choices available, then creates/follows tangents from and to, why this, why not that, then he builds. And his daughter is this SAME kind of rich thinker, broad dexterity and command of language, it’s always an inspiration to observe this secondary [primary?] level at work, separate from yet bound to the subject matter. So inspiring. Thank you Professor and Lisa.

Very interesting, thank you, Professor C. This is the only one of Forster’s books to which I never gave a decent chance – I had seen the film before I read the book, and that so stunted my visual imagination that I felt I could not assimilate the story, that it was merely a piece of literary merchandise rather than a creation with which I could interact. That is so long ago now that you have prompted me to give the book another go. I’m looking forward to your next topic.

Yours,

Dr M.

Excellent stuff; I haven’t actually read Forster, but he’s on the ever-expanding list. As always, thank you, Professor C – and Lisa. It is remarkable that you both have such a way with words, for (my) lack of a better phrase.

Was in our massive library in Jaipur and although P. consumed it without coming up for air and counts it among his very favorites, I still have yet to read it.

Now I will.

Fabulous, fabulous essay. Xo

This essay brings back memories from childhood when we visited army officers’homes full of relics from their Indian careers they lived with those memories for the rest of their lives.

I agree with Hattatts prefer the books to the film.

I have never read Howard’s End must find a copy.

Thank you Lisa & your father I always enjoy and learn much from his posts. Ida

Thank you so much for this. I’ve pulled my copy off the shelf and will try to reread it soon with this post in mind AND to check out the film. I first read the novel in my late 30s, I think, back to school to finish my undergrad. I’d been directed to it by the prof of my Commmonwealth Lit course, a gay man whose attraction to post-colonial theory/literature was its relevance to his own marginalized status. Forster’s “only connect” was hugely important to him.

Reading The Professor here on academe in the 60s, the possibility at that time of seeing its concern with homosexuality/homosociality, the Professor’s own honesty about his naïveté, I can’t help but think of Colin Firth’s splendid, devastating performance in A Single Man, and of Isherwood, of course, before him . . .

Very interesting, Professor C. Will now have to read the book. The film always bothered me, like there was something not looked at closely enough. Certainly, I was able to see that it might’ve been the relationship between Fielding and Aziz. The Stella scene seemed somehow off, and there were times that I noticed Aziz behave more as I would expect a petulent lover to behave. Alec Guinness was ludicrous. His roll should have been played by an Indian actor as I believe all the other Indian rolls in the movie were, if I am not mistaken. Having watched so many Indian films in recent months, re-watching APTI was difficult because the stereotypes seemed so much more blatant.

Thank you for giving me new eyes!

May I interject a small bit of humor here?

There were two billy goats wandering the alleyways of Hollywood when, what should they find, but a trash receptacle filled with disposed-of tins of movie film. After a pleasant nosh, one billy goat asked the other how he enjoyed his repast of film. The reply: “It was good, but the book was better.”

Thank you all so much for reading and commenting and even telling jokes. I feel extremely honored to have my father write these pieces. And I am very happy that you all appreciate his efforts, although not surprised. I’m fortunate to have such intelligent, good-hearted readers.

Professor C. says thank you too, as he reads all the comments. It appears that we will have a summer break, and return in the fall. Suggestions for the new quarter (I have to use Stanford’s system, of course, rather than semesters) are welcome.

What an excellent, insightful essay. Let me start by saying that I am Indian. I have never watched or read Passage to India. I am often reluctant to red non-indian authors take on India, especially from colonial times. I find the works to be extremely racist and bigoted – if not overtly then definitely subtly. The characters are either openly nasty or condescending towards the so called “native” population. I tried to read the secret garden and stopped out of disgust. The caste system of India is oft trotted out by westerners as an example of moral degradtion of the local social system. IMO, the british class system is worse where under the guise of equality, if someone deserves “notice” (as in simple acknowledgment of existence of that person) from another person was dependent upon his station at birth.

I guess that I should cchalk it up to various fallings of human psyche, becuase there is no denying that any Indian in the middle ages must have regarded the dirty slovenly europeans as uncouth and not worthy of notice.

Without commenting on casting of a non-indian, non-brahmin as a brahmin in the film, the correct pronunciation of Godbole is Goad-bo-lay not lee.

Similarly, the name is Gandhi! Not Gandi or Ghandi!I see this one ALL the time. Is it really that difficult or are some people really just that lazy or dumb?

This is a fascinating post. I loved both the book and the film (though Howard’s End remains my favorite Forster) and I loved reading the Professors insights.

Comments are closed.